An Interview with Ghasem Batamuntu and Will Alexander from Prague CZ

Visionary New Afrikan Jazz Poetics from South Central Los Angeles…an interview conducted by Darrell Johnson from Prague, Cz

Astral choirs chime beneath furious yet prosaic percussion, while brass as soft as palm trees on the sea of a distant planet chants. Soon the surreal Sci-fi voice of Will Alexander, begins to encant his sophisticated language of dreams while the solar brass charts of Ghasem Batamuntu and the Nu Nova Compound’s ensemble rips a hole in space.North American realms of New England, New France, Nova Scotia, New Spain have long ruled, now New Afrika has its place in the mix. That all this is beauty is emanating from New Afrikan natives of a portion of Los Angeles that has been at least twice declared a war zone in the last 50 years, may be hard to imagine. Yet burdened with a history of urban conditions that have swept from 3rd world and 1st world socio-economic extremes, to balkanized street battles for neighborhood-sized narco-states, between the cracks of civil insanity in places like South Central Los Angeles –civilization and humanity have continued to bloom…

“Remember Ornette Coleman, Charles Mingus, Charles Lloyd, Don Cherry…” Ghasem Batamuntu reminded the citizens of Los Angeles during a pre-concert radio interview on Santa Monica’s KCRW early in January 2008. Although New York and Chicago have dominated the focus of late 20th century Jazz, the Los Angeles’ South Central neighborhood was been the home of many who now are considered the leading innovators of 20th century jazz. Furthermore despite South Central’s proximity to the west coast recording industry, the roots of L.A.’s most potent music remained primarily an independent isolated community.

The similar community based results of the Chicago’s AACM, [Association for the Advancement of Creative Music] founded in 1965 are perhaps the best internationally known with jazz fans. Via the touring and recording efforts of artists like Art Ensemble of Chicago and Roscoe Mitchell, Waddada Leo Smith and others, AACM bounced from Chicago to New York City and onto the international stage. The efforts of L.A. composer and pianist Horace Tapscott though had preceded the national trend to community jazz guilds with his founding of his Underground Musician’s Association (UGMA) in 1964. AACM would follow, as would Saint Louis’ Black Artist Group, Detroit’s Creative Musician Association, and New York’s Jazz Composer Orchestra Accociation. Still despite Tapscott’s proximity the U.S. West Coast recording industry, most of the music UGMA and his subsequent Pan Afrikan Arkestra remains unknown.

“Its like this: You see how many cats are dead because they weren’t supported by their own…maybe Trane would have been alive, or Eric [Dolphy] would have been alive if first they would have been supported by their own [people]” Tapscott told Jazz Historian Frank Kofsky later in 1970. With such efforts Tapscott though was never trying for international fame, the organizational impulses in his Pan Afrikan Arkestra and UGMA were a spiritual effort to save not only his culture but also the lives of people around him. Unfortunately the sort of social cohesion and integrity Tapscott sought to bring to his neighborhood was not soon enough, in 1965 a 6 day riot broke out in Watts. It is legend that Tapscott and his band performed from the back of a pickup truck in an attempt to quell some of the lunacy in the streets, regardless in the end the business district of Watts was left in a mess of charred buildings and rubble.

New Afrikan’s did not invent rioting in California, Indian’s had preceded them centuries before in response to over 300 years of European genocide and less than civil treatment by the landed viceroys and gentry. Under banner of the United States from 1850 until the early 1900s California saw a 90% reduction of the Indian population, entire tribes were massacred in the rush for gold. Arriving to work in Los Angeles’ growing manufacturing sector, although escaping the lynch mobs of the southern U.S., California’s New Afrikan’s had more than a few reasons to be nervous. Given local police and sheriff departments that, despite some well intentioned members, had a reputation for behaving more like wild-west vigilantes than civil servants, combined with the strains of irregular economic opportunity and cultural access – many of California’s New Afrikan’s did not find a warm welcome. The separation and condensation of the races was guaranteed not only by limits of economic access, but by laws and contracts that prohibited the sale and rental of houses to non-whites in surrounding areas. Reinforced by Berlin Wall type freeway constructions, that further divided neighborhoods, such laws remained uncontested until the late 1960s. The video taped Rodney King beating that was beamed around the planet prior to the 1992 L.A. riots is only one in thousands of such stories of New Afrikan’s being ‘in the wrong place at the wrong time’.

From such conditions the voice of anger has echoed around the world entwined in the form of danceable hip-hop, while beneath the ephemeral glamour of the entertainment industry, timeless musical civilization with solid roots in Egyptian, West-African history and the evocative mytho-poetic American experience of Jazz has also emerged. This includes the ongoing evolution of the dynamic late 60s L.A. jazz that was as plugged into; the riffs of the Parliament’s Eddie Hazel, and Hendrix, as the elegance of Duke Ellington. The aleatoric advancements of Alice Coltrane’s and Pharoah Sander’s posthumous extension of Coltrane’s cosmic thread also took particularly well to the Pacific rim. This was the sort of jazz that could be heard in the streets and in the clubs of L.A. in the late 60s and early 70s. Even though artists like Charles Lloyd would take visionary risks in the clubs, the record industry was not interested. Some of California’s most potent music has never left the confines of South Central Los Angeles and its historically related sibling communities of Oakland.

Since the 80s in the United States, Batamuntu and his collaborators in community projects have promoted a combination of poetry, dance and theatre that resonate and broaden the notions revived by Sun Ra’s Olejtunde inspirations. As New Afrikan children of the 50s and 60s though Batamuntu’s generation had the advantage of living during a time when the civilizations of West-Africa and her American diasporas were slowly reclaiming more shelf space at the local library. Whereas Sun Ra had connected his African vision via details driven from Egyptian history, by the mid-60s post-colonial history met with “black-pride”, “black-power” and the inspiration of the Harlem Renaissance. In California’s sub-tropical climate all of this neatly blended with the African-Parisian-Caribbean cultivation of the literary intellectual movement known as ‘negritude’ Attributed to such writers as Amie Cesaire, Langston Hughes and Richard Wright, ‘negritude’ built on a sophisticated vocabulary of words, grammar and structure. Further informed by a history being rewritten in their lifetimes, New-Afrikan poets expanded the energetic narration and oratory that persistently has been part of Afro-american tradition.

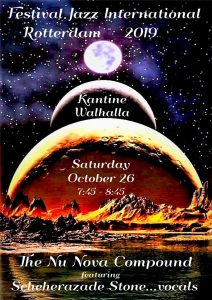

Already established as an educator, composer and session musician with a CV that includes work with Charles Lloyd, Pharoah Sanders, Sun Ra, Archie Shepp, Hugh Massakela after 20 years of touring the Middle-East, Africa and Europe—in 1992 Ghasem Batamuntu settled in Europe to catapult such New Afrikan inner-city visions into multi-media, ritual performance and cyberspace. Batamuntu’s and the Nu Nova Compound upcoming 2008 CD entitled “A gift from Trane…for Jackie”, includes the cooperation of former John McLaughlin, Sun Ra, James Newton and Charles Lloyd drummer Sonship ‘Woody’ Theus, the California piano prince Nate Morgan and former Miles Davis percussionist Jumo Santos. Besides being in the company of such jazz titans, Ghasem’s latest work contains the contributions of the literary giant Will Alexander.

Alexander’s books like ‘Asia & Haiti’, Sun & Moon Press (Los Angeles, CA), 1995 and ‘Towards the Primeval Lightning Field’, (essays), ‘O Books’ (Oakland, CA), 1998 have received wide critical acclaim. The International Biographical Centre in Cambridge, England has named Mr. Alexander an “Outstanding Scholar of the 20th Century”. Alexander’s work has been translated into Spanish, Hungarian, Italian, Romanian and Spanish and plans are currently in place for translation of his work into Czech. Currently recovering from chemo-therapy, Alexander’s New York benefit in November 2007 at NYC’s Bowery Poetry Club was headlined by his friends Anne Waldman and Jerome Rothenberg, subsequent events in San Francisco and Los Angeles also drew participation by Wanda Coleman, Clayton Eshleman and some of the West Coast’s more respected literary pundits.

With their combined interlaced literary and musical energies, Alexander and Batamuntu represent prophetic visionary American potentials. Via their experience they bring to the stage the full bandwidth of the sort of contemporary literary, jazz and visual arts inspirations Pablo Picasso found in African masks when he said…

“People had made those masks and other objects for a sacred purpose, a magic purpose, as a kind of mediation between themselves and the unknown hostile forces that surrounded them, in order to overcome their fear and horror by giving it a form and an image…At that moment I realized that this was what painting [art] was all about. Painting isn’t an aesthetic operation, it’s a form of magic designed as a mediation between this hostile world and us, a way of seizing power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires.”

In the following interview Batamuntu and Alexander discuss their art, music, poetics and the bridges they have built and continue to build between the vast lake which separates the rest of the world from the visionary futurism of this contemporary New Afrikan impulse—born of the urban islands of Oakland and South Central Los Angeles.

Darrell Jónsson: Can you tell us a little about the literary foundations of your and Will Alexander’s work, and how it first intersected?

Ghasem Batamuntu: My meeting with Will Alexander seems almost destined in retrospect. The one force responsible for the dynamics that would shape the events of our crossings strangely enough is the Watts’ riots of in the early 60’s. Post-riot events lead to the formation of the Watts’ Writers Workshop; one of many think tanks to arise after that event. It impacted me in a different but relevant manner. I was a bit younger than Will and other such notable workshop participants as futuristic literary personalities Curtis Lyle, Stanley Crouch, Ojenke Mapenzi, Kamau Daaoud, all of whom would later become very important figures in shaping the consciousness dynamic in an evolving collective movement that swept black America during that period.

DJ:The thing that is striking about both of your work, is that there is a distinct animism that is found in the better poetry and music of the last century. Batamuntu’s music avoids what the German Jazz critic Ernest Borneman called “a complexity which makes music ipso facto unintelligible for the untrained listener and thus robs the musician of the echo which he needs both spiritually and economically.” Alexander, your work as well seems to avoid, jumping on any of the typical American post-war artistic bandwagons, and seems to be all the more powerful because of it. Which brings the question, rather than mimicking or emulating the Beatniks, the Surrealists or Imagists or other ‘canons’—shouldn’t it be asked if the idea of stream-of-consciousness isn’t a natural reaction to the confluence of languages, dialects, and situations found in daily life in a place like South Central Los Angeles?

Will Alexander: For me, even the phonemes vibrate. Los Angeles naturally seems to spontaneously confirm this nomadic response by means of a nomadically functioning discourse. Unlike New York or San Francisco it functions without a recognizable locus and has developed discourse amongst a most spectacular array of human confluence. Like the city of Los Angeles I’ve had the fortune to poetically evolve without a centrifical model. I’ve not been an advocate of Rimbaud, or Breton, or Cesaire in terms of looking at their work in terms of stationary posting. What I mean by stationary posting is that their work has not enveloped me in terms of wanting to respond to their power by writing works which mirror them by replication. There never existed and continues to not exist in my spirit conservation by means of any stationary limit. I’ve always responded to language as though I were in scripting by means of improvised combustion.

GB: These streams of consciousness empty into oceans of imagination, forming a vertical beach, that erodes those tributaries of fantasy, ingrained with corral condensed to pearl.

DJ: Regardless of the of dismissal or removal of Los Angeles from much of what was the New York-San Francisco-London cultural map, you seemed to embrace the work of Aime Cesaire, which had a clear European-Caribbean-African linkage, Was part of that because Francophile Cesaire was an inspiration to refuse to stand in the shadows of Saxon culture?

WA: As Lilyan Kesteloot has pointed out “Cesaire strikes at the very heart of Western civilization, at its key value, logic…” I must say that I had come much to the same conclusion before I read him, yet I didn’t possess his maturation or the verbal substance he commanded. Reading him inspired direction in me giving me something other than the Saxon modernists to follow. For me, Cesaire remains a paragon of dissonance. When I discovered his ‘Cahier’ I was a few years younger than he was when he wrote it. To read it was both thrilling and daunting. The imagery, the unexpected leaps. It was thrilling, burning. I felt it was not only a fantastically written document but the very fiber of Cesaire’s being poetically expressed. His maturity amazed me, overthrowing the classics and the foundation which nourished them.

DJ: How about you Ghasem, in the environment of Los Angeles the Austro-Germanic musical tradition, which dominated the areas concept of ‘classical’ music or the European musical canon, must of seemed as foreign as the Anglo-Saxon literary thread? Yet from the beginning with earlier versions of the Nova projects like ‘Mezzinine’ you seemed to be dealing with some facet of ‘classicism’ in the theatrics and sound?

GB: For what you refer to as “the Mezzinine” this is not the case. Of course you could say that Max Roach was applying another approach to classical science in his investigations of odd meters he was into there at one period with his compositions featured in those ensembles with Booker Little and Eric Dolphy and Ray Draper and so with (the improv oratory of) Abby Lincoln. That is the music I grew up with and was influenced by. In that way there is a classical reference. Max Roach playing timpani in jazz music and such. Still in South Central Los Angeles classical music was always a bit exclusive, difficult to access and especially integrate into your daily movements. It was only by special arrangements normally; a school field trip for example…or some long haul by automobile of getting to a classical event, that was all in the difficulty of experiencing it; not at all like in central Europe. My composition and approach to performing in Mezzinine and subsequent projects resulted from my contemplations about finding a feel that was both West Afrikan in pulse and Afrikan American in flow. You can see much of this on youtube.com, (unfortunately the length of the Mezzinine piece forced me to edit the dance segment before I could post it). Later though there are dance segments that further heighten the rhythm contrast I was trying to highlight. The piece is actually called “Ntu the Ninth Wonder” and is intended to be an exercise and illustration in a comparative way of the manner in which odd meters and even meters shape the space you hear them in. It’s a long two cycles of nine rhythm fragment against a swinging 4/4. They each have a distinctly different shaping of the space you hear them in. The 9 is some how wider and angular with an inherent free feeling element while the 4/4 is indeed aerodynamic and slick it does not have the same sort of geodesic geometrics in how it fills the audio space. Some how it is less wide and broad yet sudden like an eel…an electric eel…while the 9 gives me a sense of timing surging and tumbling like an avalanche of poly rhythm…seeking to resolve two kinds of rhythmic presences without a loss of spontaneity…that is a conscious launching site for freer forms of rhythmic presence…

WA: Let me say that Austro-Germanic or English culture has never fomented in me a blindness for its absolutes. Of course we see its influence, year by year, fading into a kind of cultural post-mortem. Not that its completely behind us, but as I was walking in my neighborhood quiet recently, I broached the vicinity of a Muslim lady in full garb, several Korean people doing power walks, and two separate groups of Mexican people, one speaking English, the other, Spanish. America is no longer the land of two divided racial groups, one Black and one White. This old perspective has practically run its course, with Los Angeles providing a new intriguing exclamation for human possibility. It is an environment where I can verbally tap into the beyond, using English in a way that totally transmutes its Germanic heritage. This is what Deleuze and Guattarri describe as using your own language as a foreign transmission. For me, English has become a nomadic mixture of sound capable of infinite combinations. Its 26 letters can work through an infinity of combinations fueled by the sun of imaginal radiance. Its letters are not unlike the Mayan numerical code capable of moving across eons with accuracy.

DJ: Such enlivening impulses seem to be disappearing from Jazz. Here we have the issue of Central European/Slavic poetic and artistic impulses always in threat of vanishing beneath the sweep of more visible cultures, yet these very ideas have historically had vitalizing effect on the arts. Miroslav Vitous when I interviewed him 2007 was saying jazz ‘is sort of repeating’, like others he seems to be implying that jazz is dying or dead.

GB: I’d have to disagree with Mr. Vitous who I believe to be a prolific and an innovative bass player. I disagree because of the degree of musicality I see being transmitted and passed on to the next generation of practitioners. There are some really beautiful young players developing out of and extending the ideas of acclaimed maestros and masters that set out a conceptual road map before them. Master musicians like Jackie McLean and Horace Tapscott who set up community seed banks for notions and times such as these. Their conscious efforts at seeding urban fields with the bird seed and dolphin dung has created fertile soil where once only electric towers and street lamps grew. When I hear new players like Jason Moran and James Carter, the Roney Brothers, Joshua Redman, Kamasi Washington, Issack Smith, I don’t hear anything close to death unless it is ancestral and omnipresent in nature. If people feel the presence of the dead in jazz atmospheres perhaps they should see if their real estate is built on top of a graveyard. I think what he means that the business of jazz has gotten a strangle hold on the means to access the innovations that are occurring. First of all you have to realize that jazz has truly become a global expression and activity, and New York is not the only place to measure the jazz pulse. It doesn’t hold all the cards as to controlling how the general masses can access what is occurring in the music, nor is it an exclusive hive of innovative activity.

Because of it ‘s business parameters perhaps that is someplace you may hear innovations that are brought there but that does not mean the process is not ongoing in the influences of other situations. Millions of people on an island have to do something I suppose, but if you think jazz is dead then I think you should travel a bit further. I think you will find it nearly every place you go. you will see many musicians struggling still within and against a basic business configuration that limits access to innovations that are occurring outside of business concepts and formats that determine access to what sells best.

The fact that nearly a decade into the 21st century the presentation of this beautiful music is yet basically limited to environments that can not facilitate it’s potentials—because they interfere with business practice—is the dead smell in the air. There is a real necessity to try and find new and elevated life forms in the means of access to the wide variety of innovation that is a part of the living presence in the music.

A jazz club in 2008 is little more than a roaring 20’s speakeasy with a make over…maybe shredded chrome curtains instead of polyester…head mounted microphones cause that leaves more room to put in seats. There are so many more applications optional for the music. It should not be limited to 3 45 minute sets. I think by this he really means that the business of jazz is killing the music. I have a blues tune that says…”you can’t die lessen you already dead”. So don’t worry and think like that…it will kill you…if left in the grip of business concerns the progress of the music is indeed impeded. But I think it safe to say that jazz cannot die. Just like music cannot die. Wait till you hear the new Eskimo jazz with Siberian subsonics and Mongolian phase shifting. You may not be able to read it’s pulse with business radar and and x-rayed profit graphs but I can assure you jazz is tattooed upon the surface of the earth…it has evolved towards truly a human expression by embracing the human struggle of resolving the human dilemma and will exist as long as humans live…it is a gift from the gods to aid in their living long and happy lives..in several life forms…

WA: I can understand this feeling of mortality and ending when you look back on the John Coltrane band, on the worlds of Dolphy, Coleman, and Ayler, and now experience a focus more commercially shifted. We are dealing such an atomized state of affairs that insight seems tangled. The rush of the present era has created jazz studies, and not nurtured an environment where organic creation is key. But conversely, I’ve had the great experience of being the poet in Ghasem Batamuntu’s band, with stellar musicians like Nate Morgan, Sonship Theus, and Roberto Miranda. These particular musicians remain active, and Jazz music remains active, maybe not in the concentrated way that previous bands performed night after night, but in the sense that its powers of improvisation continue to prevail. It’s like trying to suppress nature for a time, but yet it is always there, ready to burst forth from suppression as uncontainable quanta. For me, to improvise is to breathe, so when I listen to my inner verbal forces, they start to flow on the page as inevitable pyroclastics. Jazz, improvisation, remains a living essence, which will, over time, reassert itself as a necessitous power in the human continuum.

DJ: Ghasem, how has your sound evolved in recent years?

GB: When I lived in Amsterdam I played in the streets quite a lot as well as at the North Sea Festival or the Bimhuis. Amsterdam is a quite patronic and social urban contour so people are out in the streets and active in a civil manner more than in many of the urban centers I’ve visited. Anyway, there is a lot of water, and morter, and brick integrated into the architecture and landscape of that canaled grottopolis which also dilates the acoustics of sound. But in a very organic manner as opposed to electronic. So there in Amsterdam is a natural reverb and delay that echos between the brick palaces and financial centers…in the tram stations…and pleins where the public gathers. I became intrigued with this sound but could never reproduce it say in a jazz club there…you were lucky if you got a sound system that performed in a balanced manner. I grew up in the 60s so Jimi Hendrix was like one of those tribal Dogon ceremonial deities that you were lucky to experience once in a life cycle…just like Coltrane, Sun Ra, or Cecil Taylor, they ooze like sap from a tree at a particular moment in time. And then it’s not like that again until the next occasion…anyway he gave perspective to the dilation of sound I am making reference to. So with the advent of the digital tonalities that are condensed in these various devices available today you can more or less deconstruct and reconstruct sonic cells and particles…I hear music from the mountains of Japan and Mongolia that have that organic resonance…the aboriginal approach as well.

Anyway I have been busy with trying to recreate that sound of playing outside with the soprano saxophone mostly these days…around the time of the Mezzinine clips I was experimenting but since then there have been lots of new technical developments. As well I’ve constructed a few acoustic wind instruments and when played thru various simple electronic devices the sonics are increased to prehistoric proportions allowing the imagination to place them in unexpected scenarios…like some ancient birds or wild beasts howling from the darkness of the jungle canopy…it reinforces the images that appear suddenly in the poetry. Lately I have been contemplating a vertical beach…it is an experience easier to describe thru sonic associations than any given linguistic

DJ: Here it seem Ghasem you find some clue to the adaptation or mediation of his changing environment, via a strong reference to a pantheon of functional heros. So where does this division land ; between totemic symbol as spiritual and technical reinforcement, and totemic symbol becoming a rigid dogmatic monolithic pantheon. A body of dogmatic style and symbols that is then then used to reduce the natural human will and imagination and the 10s of thousands of years of linguistic use and development as a side show – reduced to something people need to put a face on, name on, package and either worship or commercialize. What about the intonations of living ancestors as well, and the dramaturgy of everyday life, how do you weigh these factors into your sense of poetics?

WA: Because the conscious mind is so prevalent in the West there is always the predilection towards dividing and stratifying people and objects and feelings. Because I feel such distance from such judgments I see everything as being alive, not from a strictly optical presence. For me, there can exist no surcease, no eternal divide between beings who have died, and beings who live, and beings who are yet to be. As in African animism all is alive, therefore each leaf, each cry of a bird, possesses an organic inner balance. This is the momentum at the core of my writings. Life is constantly applicable. That is why I possess dictionaries on everything, from medicine, to astronomy, to warfare. Not just an inscrutable kindling, but like the colors in a Miro or a Jackson Pollack painting, words in a text must poetically balance. So each article is as essentially charged as some far reaching term aptly put.

For me, language must psychically cohere in all its disparate parts. It is an illuminant endeavor, a life which resounds as encompassing auditory health. This is quite the opposite of works promoted for strict commercial consumption where a momentary style and obsolescence is key. This latter seems a world of simulacra and superficial consent.

When I speak of Bob Kaufman, or Philip Lamantia, or Aime Cesaire, they are never monuments monomial in demeanor. Instead, they emit a living radiance. During my poetic inception they were my primal guides. They’ve allowed me over time to attain a boldness in my research and expression. Their works for me have been nothing less than transporting.

They opened me up not only to my subconscious ethers, but also sparked flight in my supra-conscious mind. It could be said that by reading them it opened another understanding so that when I read Sri Aurobindo’s The Life Divine, I then understood language as infinite circuit capable of movement between the subconscious, conscious, and supra-conscious mind; an understanding practically unbroached in the West.

Knowing the works of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Gogol, and Dostoyevsky alerted me to the fact that a dissonant intelligence was already at war with Europe. I knew the incandescence of Blake, the poetic blaze that was Shelley, and was able to see the connection between their seeds of dissension and the eruption of Surrealism many years later.

DJ: Do you think it would have been possible to arrive at a similar place without an index to Parisian trained or European based literary figures?

As for Paris, Breton, Leiris, and Artaud remain essential for me. What Artaud and Leiris expressed was not unlike the Afro-centric revolt one finds in Cesaire’s Tropiques. Also the examples of the painters Miro, Vlaminck, and Masson have greatly moved me. What I’ve found is that Los Angeles seems akin to an earlier era in Paris, with its animisms, with its infinite dialects of the psyche. From the beginning of my poetic odyssey I always sensed a nascent liberty which existed through language. But no matter how free, how inclement the power of one’s lingual premonition, it needs time and experience to fuel its metamorphosis. No matter what some quotidian detractors may claim, reading remains a powerful component of the human experience. It is absolutely essential for poets especially in their developmental stages.

GA: In the pursuit of poetic portal as dharmic inertia, equating suddenness with improvisational music skills…feeling enough about the language to barely hold on to it’s flow it’s letting go I take spontaneous direction and instantaneously at the speed of concept embody it with the arrived logic and give it a life thru communication…association…application thru the dharma of our muse.

DJ: Nowadays university scholars are calling (an overdue) observation that European culture is Euro-asian in fact, if one counts the historical symbosis of science, industry and the arts. The moniker of Euro-Islamic civilization is nearly as accurate but far more controversial. Egypt though is the most accessible symbol Africa provides us with towards Euro-African civilization, particularly with the influence on Greece the ‘classical world’. How in your lifetimes have you seen and expanded definition of Yorurba and other sub-Saharan civilizations towards informing the impulse of Afro-centrism?

WA: The oldest nation on record to date was the Nubian nation Ta Seti” located to the south of Egypt. This reality remains a source of power for me. I feel that I emit its original rhythms through the voice in my writing. Not didactically mind you, but by the improvised spontaneity found in my instinctive verbal actions. I feel as if I am commingling my powers with a primordial electrics so that everything I write trembles with the quickness of lightning. When I say this I am not trying to invoke some kind of superior literary largesse, thereby aligning myself with some chronic literati competitive with exhaustion. But like Cesaire I seek to engage the electricity of the total environment. This for me remains African; understanding the palpable world by means of its inner grounding this being analogous to the natural respiration operant in the powers of true poetic creation.

DJ: Earlier I mentioned the ‘classic’ elements in some of Batamuntu’s work. Especially when dance, poetry and music all combined, I do see something ‘classic’ as well in these collaborations you have done together like Solea on the upcoming CD. Here I find that sense of what Harry Partch called ‘corporeality’ that in Europe is historically found in the theatre of Greek antiquity. Via my studies in ethnomusicology though, every year there seems to be new links tying the ancient music, science and culture of North Africa to that of what is called ‘classic’ Europe. How do you see the global influence of Africa on the arts both ancient and modern?

WA: There is no question that Africa has fueled not only the arts in the modern European movements, but also the arts and knowledge of the planet. There is no mistake that when entering a philosophical seminar in the West, one is never allowed proper entry into the proto worlds of the Pre-Socratics. As the scholar Asa Hilliard points out, that Egypt “was the parent of other systems of education, especially early Egyptian education in Greece and Rome.” Education “was not seen as a process of acquiring knowledge” but “was seen as a process of the transformation of the learner.” According to Plutarch, Solon, Thales, Plato, and Pythagoras found their original maturation not upon the soils of Greece, but in incandescent halls provided by the Pharaohs. We see the rhythmic source of Africa, in sculpting, in the dance, in the verbal arts. In Europe one need go no further than Vlaminck, Picasso, and Leiris to see its profound influence on expression in modern art. And it remains essential to this hour, even if its legacy seems willfully minimized by the residues which still inform the post-colonial West.

GB: Africa arrives through illustrating an equating of an embodiment of the spirit…an obsevered dilation during the process and interaction of parallel inertias ascending and decending upon the same moment of intent thru an opal portal poised in complex rhythm. Structures pulsating prior to propolsion…John Coltrane’s meditations in Seattle with Juno and Olatunge, Sun Ra’s Egyptian Echoplex, Cecil Taylor surrealistically twisting time around grenadilla wood and ivory…humming a bird song for Henry Dumas and Mori Konte.

Over 70 works by Ghasem Batamuntu, Will Alexander and their affiliates can be seen and heard at;http://www.youtube.com/nuranusvortex